- Home

- Angela Jean Young

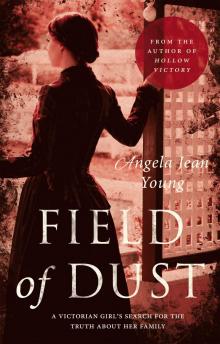

Field of Dust

Field of Dust Read online

Field of Dust

Based on a true story

Angela Jean Young

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

The Book Guild Ltd

9 Priory Business Park

Wistow Road, Kibworth

Leicestershire, LE8 0RX

Freephone: 0800 999 2982

www.bookguild.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @bookguild

Copyright © 2017 Angela Jean Young

The right of Angela Jean Young to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This is a work of historical fiction based on fact. The key characters were members ofAngela Jean Young’s family, others real people central to their lives. Every effort has been made to preserve the integrity of those referred to in the text. Otherwise, any resemblance to actual persons is purely coincidental.

ISBN 9781912362882

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

To the memory of Florence Gant.

I remembered the time when the village of Northfleet consisted of a few houses on the shore, together with those on the hill above, where then there was a little village green, now alas! only a field of dust.

The Reverend Frederick Southgate

Vicar of St. Botolph’s, Northfleet, 1884

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

1

‘Come on, Floss, your mam won’t be out for ages yet… it’ll all be over if we don’t hurry up.’

Jessie Larkin sounded really fed up with her friend. Several times that afternoon, she’d been back to the same spot outside The Huggens Arms where Florence Grant was standing under the hanging lamp. Shivering with the damp riverside air permeating her threadbare pinafore, no amount of gory detail could tempt her away from that spot. Flossie knew better than to disobey her mother.

‘It’ll be worth a clip round the ear, I promise,’ pleaded Jess. ‘Our Arthur reckons he could see dozens of bloated bodies. Henry Luck’s been keeping a tally. We had to hold our noses when the barge went by the first time. Piled high, it was. There’s bound to be loads more by now, my pa says. They’re coming up early with the sewage.’

It was all too much to bear. Flossie dropped the balls of cement clinker she’d been idly smashing to dust against the pub wall and ran off after Jessie. After all, there was a good chance she’d be back before her mother’s money ran out. If it bought her more than five gins, Mary Grant wouldn’t remember that she’d left her daughter outside the pub anyway.

The girls clambered onto the slippery landing stage at Robin’s Creek and joined the throng of excited children perched on the end, so as to get the best view round the bend of the river.

‘Look,’ shouted Henry, pointing with a piece of rotting driftwood. ‘There’s more. Cor blimey, they looks like they’re about to burst.’ Pushing his cap sideways he puffed out his cheeks in demonstration. The other kids laughed, the girls squealing as their favourite jester teetered precariously close to the edge.

‘Don’t be falling in,’ shrieked Maisy Turner, ‘or you’ll end up like one of them.’

The children were hardened to seeing dead bodies floating in the Thames. Travelling downstream on the tide, they would often get wedged under moored vessels in Northfleet Harbour and remain stuck there for days, the putrid smell finally giving them away. It happened all the time. The bustling London docks were dangerous places to work – a docker misplacing a step with a heavy load could disappear without trace. All too frequently the bodies of frail women would be hooked out of the river, their haunted faces revealing the desperation that led them to suicide. Waterloo Bridge wasn’t known as the ‘Bridge of Sighs’ for nothing.

But this was different. Henry had been keeping a tally on the side wall. So far two hundred had been chalked up, fifty of them children. For hours he and half his school class had watched, transfixed by the gruesome sight of tiny bodies dressed in their Sunday best bobbing past the bottom of College Road, their bloated parents rising and falling around them.

‘I’d better be going,’ Maisy Turner said reluctantly. ‘My tea’ll be ready.’ Some of the others followed her up the slope, carefully picking their way round piles of rotting seaweed and kicking up cement dust to hide the blobs of tar on their boots so their mothers wouldn’t notice.

‘I’m not going anywhere,’ Henry shouted. ‘Bevan’s Spry’ll be back soon. Not missing that for all the tea in China. She’s brand new.’ With that he plonked himself down on a rusty mooring bollard and gazed out across the misty river, searching for the brown sails of the empty Thames barge. Its crew had been coming and going for days, dragging unfortunate victims of the disaster out of the disgusting water. Built for transporting barrels of cement, this was a dreadful first assignment for the vessel and its crew.

It had been a week like no other. Rumours were rife about the demise of the paddle steamer SS Princess Alice. Flossie had heard no end of different versions of the tragedy. It was hard to take in because, only six days earlier, on Tuesday 3rd September 1878, she and Jessie had been standing by the smart pier gates – as they usually did after finishing their chores – watching the happy hundreds exiting the tunnel leading from the famous Rosherville Pleasure Gardens to pile aboard the doomed wooden pleasure boat. There was always a chance someone would throw away a programme, or better still, discard a hastily bought souvenir as they rushed through. It was a pleasantly warm evening and the girls stayed until the very last person boarded the packed vessel.

The Alice was making a routine ‘moonlight trip’ from Northfleet to Swan Pier near London Bridge. Hundreds of Londoners had paid around two shillings for the return fare to visit the gardens. Close to Woolwich town she collided with the collier Bywell Castle, splitting her in two just behind her starboard paddle wheel. The lightly built Alice didn’t stand a chance against a ship that was four times bigger. It took her less than five minutes to sink to the bottom of the river. A hundred or so were rescued, clinging to bits of flotsam, but 650 lost their lives.

Flossie wept when she heard her father reading out the horrifying details from the local paper:

‘Soon policemen and watermen were seen, by the feeble light, bearing ghastly objects into the offices of the Steam Packet Company. A boat consignment of the dead contained mostly little children, whose light bodies and ample drapery had kept them afloat even while they were smothered in the festering Thames. A row of little innocents, plump and pretty, well-dressed children, all dead and cold, some with life’s ruddy tinge still in their cheeks and lips, the lips from which the merry prattle had gone forever. It was a spectacle to move the most hardened official and dwell forever in his dreams.’

Stories quickly circulated

about the paddle steamer being overcrowded and not properly manned, as well as reports that the pilot of the Bywell Castle had failed to realise the danger soon enough. Everybody was blaming everybody else. One thing was certain, though: this part of the river was one of the most polluted in the country. Industrial waste and raw sewage were frequently pumped directly into it. Not only did this contribute to the high death toll of those who went into the river, but it caused sunken corpses to rise to the surface after only six days, rather than the usual nine.

‘Here it comes!’ Henry yelled, leaping off the bollard just in time to see the small mizzen sail being raised to help the flat-bottomed barge swing round into the harbour.

Arthur had been right, there were still an awful lot of corpses floating in the murky water and the smell was dreadful. The sound of the tiller being pushed over signalled the massive vessel coming about. Henry eagerly grabbed at the rope being hurled ashore, but it was so heavy, it knocked him over. The girls gasped as they watched it slither into the river and the barge lurch on the tide. Some of the boys dashed to help pull the sodden rope back up just as a deckhand leapt ashore, effortlessly dragging it out of the water and twirling it expertly round the bollard.

Trying hard to regain his composure, Henry banged his cap against the harbour wall, creating a cloud of cement dust that was so dense it made them all cough and rub their eyes.

‘I could have done that, I know about knots,’ he said unconvincingly, the boast making little impression on his dwindling audience. ‘My grandpa used to make rigging for Pitcher’s in the old days. His shipyard built Navy gunboats. Had sixty-eight-pounder cannons, they did.’

The children had heard all it before, and as the last few turned to leave, Henry tried a final tack: ‘My Uncle Tom’s taking me up Woolwich later when his shift’s over. On the train. Won’t be the first time for me, of course. Any of you lot ever been on a train?’

Jessie raised her eyebrows at Flossie. Henry was such a braggart. Only a few of the kids from around The Creek had ever been on a train. The closest they ever got to one was watching from the bridge above the chalk cutting as the puffing giants forged their way to and from Gravesend. Flossie knew only too well what it meant to go home peppered with coal smut on her clothes – invariably a good slap on the backs of her legs.

‘What’s up Woolwich, then?’ Albert Bull replied inquisitively.

‘Bit of the Alice,’ Henry shouted back, pleased that at least someone had responded, even if it was only his steadfast best friend. ‘The paddle wheel. It’s beached, so we have to go while the tide’s out. Tell you all about it tomorrow.’ With that he skittered off along the jetty and disappeared around the corner, heading for his cottage in Dock Row, with loyal Albert, as always, trailing along behind.

‘Think I’ll go to school tomorrow,’ said Jessie as they picked the seaweed off their boots outside The Huggens Arms. ‘The class will be excited when they hear what we’ve seen. Will you be coming?’

‘Depends if my mam’ll let me,’ Flossie replied dejectedly. ‘There’s the lodgers’ washing to do.’ Unlike her friend, Flossie would willingly have gone to school far more often, if allowed.

‘Well, it looks like she hasn’t found you missing. You could hear her singing a mile off. Do you want me to wait with you? No telling what she’ll be like when she sees daylight now.’ Jessie put her arm protectively around her friend’s shoulder.

‘No point in both of us getting what’s coming,’ Flossie sighed, resigned to her fate.

The girls had been friends from the minute they’d laid eyes on one another. Both lived in The Creek or ‘The Crick’ as it was called by the locals, here on the Kent side of the River Thames. Originally just a few dwellings constructed around boatbuilding yards, the street had gradually expanded after a local man, James Parker, set up his Roman cement business there. Twenty-five years later, better quality Portland cement had taken over. Cheap to make and highly profitable, it was now in mass production with nine cement factories operating in Northfleet. Each one needed a vast army of men, whose main requirements were sufficient brawn and endurance to stand up to the heavy labour required.

The Creek by this time was a bustling row of forty-six ‘cottages’, three alehouses and a grocer’s shop, each dwelling bulging at the seams with large families and lodgers. Jessie lived at number 7, between The New Blue Anchor and The Huggens Arms. Flossie was further along at number 30, next door to The Hope. Despite it being Mary Grant’s true local, Charlie Baker, the long-suffering licensee, had finally told her never to darken his door again.

‘I do not wish for such blasphemy to be heard by my eight offspring,’ he had made clear to her as she was finally ejected. So The Hope had to be given a wide berth – especially when the pub’s Irish lodgers – the two Patricks, Murphy and Delaney – were in charge. It didn’t do to mess with them, that was for sure.

Along with her ma and pa and siblings, Jessie had been born in The Creek. This wasn’t the case with Flossie. Her memories were a bit hazy, but she vaguely remembered travelling with her younger sister Lottie, when she was about four, from a place called Ipswich. All she could recall was clinging on to her father for dear life amid all the pushing and shoving, being crammed into a cold, uncomfortable carriage and engulfed in choking smoke as it thundered out of the station. She’d been on a train all right, but it wasn’t something she was going to share with Henry Luck. She couldn’t recall any other details and there was never any talk of the past in her house. Children learned the hard way not to ask too many questions.

The sun was low in the sky before a dishevelled Mary staggered out of the public bar, her thick, wiry hair shedding the pins that had secured it in a bun. Squinting at the fading light, she beckoned to her daughter for support. With the drunken woman leaning heavily on her as they lurched down The Creek, Flossie battled to keep them both upright. Spotting Bessie Turner scrubbing the step of number 19, Mary pushed Flossie aside and wobbled across the granite chippings into the middle of the street. With hands on hips, she uttered some kind of profanity before almost falling backwards into a huge hole full of mud.

‘Don’t you go shouting the odds at me, Mary Grant,’ Bessie screeched, pushing herself up from the boot scraper and hurling the carbolic soap into her metal bucket. ‘You should be at home cooking your husband’s supper. Whistle’s about to blow, you know that.’

Poking her head out the door to see what the commotion was all about, Maisy Turner sheltered behind her mother’s skirts on witnessing the state Mary was in. It was all too common an occurrence. Raising her eyebrows at Flossie, Maisy retreated into the house, coarse dripping still smeared around her mouth.

Flossie had just managed to get her mother inside their own front door as the whistle finally blew. A chorus of whistles, actually, from the half-dozen cement factories all within earshot. Luckily, her sister Lottie had already laid out the few meagre scraps from the pantry for their meal, and so between them they were able to prop their mother up in her chair, hair restored to a semblance of order, before their father’s familiar footsteps were heard outside the window.

The end of the working day was quite an event. Mothers would rush to drag their children off the street as dozens of men criss-crossed The Creek from all directions, cement dust cascading from their caps and shoulders. The same scene could be witnessed in all the surrounding streets and alleys. With bodies too tired to linger and throats too parched to speak, they’d quickly disappear behind their front doors. In no time the street would be deserted again, leaving a trail of footprints in the thick new layer of grey dust. It was a sight to behold. Blink and you’d miss it.

Like so many itinerant workers, Samuel Grant had heard about the need for men in the burgeoning Northfleet factories whilst struggling to make a living in Ipswich. He, Mary, Flossie and Lottie had arrived with virtually no money and little idea of what they would find. That was five years ago. The Knight

, Bevan & Sturge factory, which came right up to the end of The Creek and towered over their rented house, had offered him a job on the spot. Still in his twenties and thankfully fit and strong, he was put to work unloading blue clay from barges arriving at the wharf. Dug from the marshy banks of the Medway, sometimes eight feet thick, Sam had to use a spade to cut it up – much like butter in a grocer’s shop – and then load it onto wagons pulled by powerful horses. It was back-breaking work and he worked every shift going, yet rarely had any money left in the coffers. Mary saw to that, in The Huggens Arms.

Holding open the front door for the three lodgers who worked alongside him, Sam kicked off his well-worn hobnailed boots and threw his cloth cap onto a wooden stool in the corner of the kitchen. The other men followed suit. Flossie filled a tin bowl with warm water from the range and she and Lottie watched as they washed their hands and faces, their pallor gradually returning to a healthy pink. Desperate to tell her tale of bodies and bonnets in the Thames, Flossie knew she’d have to wait until they were all seated around the table and tucking into their much-needed bread and smoked bacon. She just had to hope her mother didn’t wake up and start holding forth.

Later, the girls carried the washing bowl across the pebbles and emptied the powder-grey water into the river, there being no fresh water available. They were used to having to do it. Rapid building had resulted in cesspits being dug within feet of the wells. The previous year, ten months had passed without any water at all while everyone argued about the water being contaminated and who was going to pay to put it right. They had been forced to fill their buckets from wells belonging to the landlord’s other tenants, a fair walk away.

As she washed out the last dollops of cement, Flossie caught sight of old Annie Devonshire from number 35, making her way towards them, waving her stick.

Field of Dust

Field of Dust